An algorithm is traditionally defined as:

a finite, well-defined sequence of computational steps that takes an input, performs a series of operations, and produces an output.

This doesn’t really tell us what an algorithm is in practice, however. We encounter algorithms every single day. If you have ever driven on a road with a traffic light sensor, then you have interacted with an algorithm. The sequence begins when you arrive at the stop light, perhaps dependent on it being a certain time of day. From there, a set procedure begins:

- Detects whether something is there

- Determines if and how long the light should change

- Changes the light for that predetermined duration

- Repeats as necessary whenever the sensor is triggered

On a social media platform, this looks more like:

- Detects traits or variables about a user

- Determines what content should be prioritized

- Changes the content and measures user interaction

- Repeats as necessary to alter the user’s feed

Of course, these are examples of classical algorithms. You simply tell the algorithm what you want it to do based on certain triggers and it sets them into motion. You can explore this even further on social media by creating an alternate profile and changing the way you interact with content. It will alter your entire feed and curate it to you based on that, via the use of algorithms. I don’t recommend exploring algorithms at a stop light. It could be dangerous.

So, why and how exactly are quantum algorithms different than classical algorithms?

Quantum vs Classical Algorithms

There is quite a big difference between how a quantum algorithm operates and how a classical algorithm operates. In classical computing, a lot of what happens is very siloed and separated. We built architecture and processes that were fairly two dimensional. So, as you saw above, the steps involved with a classical algorithm running are very linear.

With quantum algorithms, we do not get that siloed step by step process. We instead get a sort of living organism of events that unfold. The reason for that is, that much of quantum algorithms rely on qubits being in superposition. There are probabilities we can influence and guide to certain outcomes, but we can’t tell a qubit in superposition exactly what it will collapse into, otherwise it would already be a classical bit. This may seem like a disadvantage at first glance, but it is something we can use to our advantage. So, it is imperative that we understand the conceptual mechanics behind the process to grasp how quantum algorithms work.

First, let’s discuss the underpinnings of both types of algorithms so we can see exactly where they begin to diverge. And that process occurs before the algorithm is ever activated at a lower level where data analytics and pattern recognition happen.

So, if what happens at the stop light after you arrive there is the algorithm, the transformations happening before that are the analytics of traffic patterns and how traffic is flowing at different times of the day, week, month, and year. These analytics and data determine which algorithms would be most effective if implemented and at what times to implement them to be most effective. So, what do we call the backbone of this process in classical and quantum computing? FT and QFT. The concepts have some similarities in name, but in practice they operate quite differently.

FT and QFT

Underneath both quantum and classical algorithms, we see the use of FT (Fourier Transform) and QFT (Quantum Fourier Transform). In classical computing FT was used for signal processing, solving differential equations, and pattern recognition. Algorithms rely on these analyses in order to function. For example, DFT (Discrete Fourier Transform), a specific type of FT, is used to extract data and manipulate patterns. It could, for example, analyze a pattern and determine when a user was most vulnerable to specific content being displayed based on analyzing that pattern. Then, an algorithm could be triggered based on those conditions to display specific data to the user. What is displayed could be an advertisement or something more nefarious, such as a cognitive attack designed to influence a user’s psychological or emotional state. The first widely reported uses of these types of tactics occurred during the controversial Cambridge Analytica attacks and the resulting political influence campaigns. Since then, they have become both quieter and more dangerous.

We know how the underpinnings of classical algorithms work because we’ve seen them in action. And if you didn’t know, you now have a much clearer picture. So, how are these analytics derived and interpreted in quantum computing? With the use of QFT, as opposed to FT. So, let’s dive into QFT conceptually.

Quantum Fourier Transform (Operation)

What is QFT?

By definition:

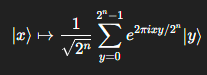

a linear transformation on quantum bits (qubits) that maps a quantum state representing a sequence of amplitudes in the computational basis to a new quantum state in the Fourier basis. Formally, for an n-qubit state ∣x⟩, QFT transforms it as:

QFT is the quantum analogue of the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) used in classical computing. It is a fundamental operation in many quantum algorithms, such as Shor’s factoring algorithm, because it efficiently extracts periodicity and phase information from a quantum state. Unlike the classical DFT, QFT can be implemented with O(n2) quantum gates on an n-qubit register, offering exponential speedup over classical Fourier transforms for certain applications.

And, what does that mean in application? Fortunately, we don’t have to be mathematicians or physicists to understand what is going on here. But, we do need to know what amplitude sequences, the Fourier basis, periodicity, phase information, and n-qubit states are conceptually to begin.

State Related Concepts: N-Qubit States, Amplitude Sequences, and Phase Information

N-Qubit States

Definition:

The combined state of n qubits, representing all possible configurations simultaneously in superposition. In practice, n-qubit systems are almost always three or more qubits interacting, which enables meaningful algorithmic structures to emerge.

Explanation:

Think of an n-qubit state as a “container” system holding all possible outcomes that the qubits could collapse into when measured. For example, a single qubit can be 0 or 1, but two qubits together can represent 00, 01, 10, and 11 simultaneously. The n-qubit state gives us the complete picture of all these possibilities at once.

Amplitude Sequences

Definition:

The probability weights associated with each possible qubit configuration in a quantum state.

Explanation:

Each possible state in an n-qubit system has an amplitude, which is a complex number containing both magnitude and phase information. (The squared magnitude gives the probability of measuring that state, but the phase is what allows quantum interference to occur.) These amplitudes are what QFT manipulates to reveal hidden patterns in the quantum state. Recall that in earlier parts of this tutorial, we discussed probability amplitudes and how we can influence them using quantum gates and what weights were associated with certain outcomes.

Phase Information

Definition:

The relative angle or “timing” of each amplitude in the quantum state.

Explanation:

Phase is crucial in quantum computing because it determines how different components of a quantum state interfere with each other. Recall, we went over constructive and destructive interference in previous parts of the tutorial. By adjusting and analyzing phase, QFT can extract periodic patterns that would be invisible if we only looked at probabilities (amplitudes) alone.

Transformation Related Concepts: Fourier Basis, Periodicity, and Computational Basis

Computational Basis

Definition:

The standard basis of a quantum system, typically represented as the binary states 0 and 1 for each qubit.

Explanation:

This is the “original coordinate system” of the qubits. Before QFT acts, all quantum information is expressed in this basis. You can imagine it as the default way the computer “sees” the qubits before any transformation occurs. It is also the basis that qubits collapse into upon measurement from superposition. The classical results of these measurements are then used to determine which gates to apply in order to adjust amplitudes and phases, such as during teleportation.

Periodicity

Definition:

The repeating structure or pattern in a quantum state that QFT can detect.

Explanation:

Periodicity is what many quantum algorithms are searching for. For example, Shor’s algorithm uses QFT to find the period of a function, which then allows efficient factoring of numbers. You can think of it as the “hidden rhythm” in the data: a repeating pattern that is extremely difficult to detect classically. Revealing these periods exposes underlying structure, which is why QFT is so powerful both for exposing weaknesses in cryptography and for building cryptographic subroutines that are aware of those structural properties.

Fourier Basis

Definition:

The new basis that results from applying the Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT), representing a quantum state in terms of frequency components rather than raw 0 and 1 states. In this context, “frequency” refers to how often a pattern occurs, such as in a repeating structure (periodicity) in the quantum state.

Explanation:

When we transform a quantum state into the Fourier basis, we are changing perspective: instead of looking at individual qubit values, we see the underlying periodicities and patterns in the state. This is what makes QFT so powerful for tasks like factoring large numbers or finding repeating patterns in data.

Conclusions about QFT

In classical computing, we sometimes use the Fourier Transform to gain structural or systemic insight—but that insight relies on observed, concrete inputs. With the Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT), the inputs themselves are in superposition and not directly observed. Instead, we focus on the relationships, patterns, and periodicities inherent in the system to draw conclusions about specifics.

This allows us to work backwards from the patterns, revealing hidden structures in the data. From these patterns, we can determine which quantum algorithms are most effective for the situation at hand. It’s a top-down approach, analyzing the system’s global behavior first, rather than a bottom-up approach that builds only from individual outputs. And when algorithms are combined with the systemic perspectives provided by QFT, it becomes possible to influence and guide the behavior of the entire quantum system, rather than focusing on individual inputs and outputs.

Algorithms as Keys for QFT

Let’s go back to the traffic light example. In classical computing, the Fourier Transform (FT) is like analyzing how many vehicles pass through a traffic light and at what times. You’re working with observed outputs, counts, timing, and frequencies derived from what already happened.

The Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT), on the other hand, is like analyzing the entire geographical area’s traffic patterns at once. Instead of focusing on individual intersections, you examine how all roads, lights, and traffic flows interact. From that systems-level view, you can deduce how traffic light configurations are structured and coordinated. Looking at the whole region gives far more insight into what is happening and why, not just the surface-level results.

A similar idea applies to cryptography. We wouldn’t want to create a million keys and try each one in a lock. That’s brute force. Instead, we’d analyze the lock mechanism itself or a family of lock mechanisms to understand the underlying principles. Once you understand the structure and patterns that generate the lock’s behavior, you can develop a method that bypasses the lock mechanism, rather than focusing on a key.

We begin by understanding the entire environment around the locking mechanism and the lock itself. QFT gives quantum algorithms their eyes; without it, they’re operating almost blindly. In one algorithm family group, this corresponds to identifying a Hidden Subgroup Problem (HSP). The Quantum Fourier Transform exposes signatures of this hidden subgroup in the system’s amplitudes. From there, we can determine the most effective algorithm to carry out the desired next-step procedure.

Quantum Algorithms and Their Uses

Let’s begin by breaking Quantum Algorithm types down into sections by their functionality: Cryptography & Number Theory, Search & Optimization, Simulation & Modeling, and Linear Algebra & Machine Learning

Cryptography & Number Theory [HSP Family Algorithms]

This category focuses on algorithms that exploit mathematical structure such as periodicity, modular arithmetic, and hidden relationships within numbers. Quantum algorithms in this space use QFT to reveal patterns that are infeasible to detect classically, enabling tasks like factoring large integers and solving discrete logarithms. These capabilities directly impact public key cryptography, both by exposing weaknesses in classical schemes and by informing the design of post quantum cryptographic systems.

Shor’s Algorithm

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Helps uncover hidden patterns in numbers via periodicity, which makes factoring large numbers much faster than classical methods.

- While famous for its impact on classical cryptography like RSA, it’s also valuable for mathematical research and studying repeating structures in complex data.

- Serves as a research tool for exploring how quantum algorithms work and testing new techniques in quantum computing.

How it Works

- Finds repeating patterns in a number-based function using the Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) and HSP.

- The algorithm focuses on the structure of the problem rather than checking every possibility individually, revealing the solution more efficiently.

- Combines quantum pattern detection with classical steps to get the final answer.

When to Use it and Why

- Use when analyzing cryptography systems that rely on large numbers, or when studying hidden patterns in mathematical structures.

- Ideal for research and testing in quantum computing and algorithm design.

- Powerful because it looks at the whole system and its patterns instead of relying on trial-and-error approaches.

Simon’s Algorithm

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Finds hidden structural relationships in a system, rather than focusing on numeric periodicity.

- Classically, discovering these hidden rules requires checking exponentially many possibilities, but Simon’s algorithm does it efficiently using quantum superposition and interference.

- Useful for research in quantum algorithms, exploring interference-based problem solving, and understanding hidden structures in data.

- Hidden patterns, or ‘hidden strings‘ appear in everyday computing whenever there are repeated or correlated behaviors not obvious from individual outputs, like duplicate database entries, error-correcting codes, repeated logic in software, or structured patterns in large datasets.

How it Works

- Prepares all possible inputs at once in superposition and queries the function, creating interference patterns that encode the hidden relationships.

- Measurements gradually reveal information about the hidden pattern, letting the algorithm deduce it efficiently.

- Unlike brute force, Simon’s algorithm leverages the system’s global structure, exposing hidden correlations without inspecting every data point individually.

When to Use it and Why

- Use when you suspect there’s a hidden relationship or rule in a system that would be slow to uncover classically.

- Ideal for research, algorithm testing, or analyzing datasets with repeating or correlated behavior.

- Powerful because it extracts structural information efficiently, rather than relying on trial-and-error or examining outputs one at a time.

Hidden Subgroup Algorithms (HSP) [Umbrella of Hidden Rules]

Primary Uses and Improvements

- HSP is a general framework for quantum algorithms that seek hidden rules or structures in functions.

- Many famous quantum algorithms are special cases of HSP, making it a central concept in quantum computing.

- Solving HSP allows algorithms to reveal secret rules governing systems efficiently, rather than inspecting each output individually.

How it Works

- Start with a function whose outputs are structured according to some hidden subgroup or rule.

- By querying the function in superposition, interference patterns encode information about the subgroup into the amplitudes.

- Clever measurements extract the hidden structure, letting the algorithm uncover the secret rule efficiently.

- The main idea: the algorithm focuses on the system’s global structure, not individual outputs.

Connection to Specific Algorithms

- Shor’s algorithm: HSP over integers. The hidden subgroup corresponds to the period of a function, which allows factoring of large numbers.

- Simon’s algorithm: HSP over binary strings. The hidden subgroup corresponds to a hidden string that links inputs together, revealing structural correlations.

- In other words: HSP is the container; Shor and Simon are specific ways to uncover hidden rules depending on the type of data or structure.

When to Use it and Why

- Use HSP when you suspect a hidden structure or rule governs a system or dataset.

- Ideal for cryptography, number theory, combinatorial problems, and datasets with hidden correlations.

- Powerful because it provides system-level insight, letting algorithms exploit the structure rather than brute-force the outputs.

Intuitive Process Flow

- QFT → transforms the qubits from the computational basis into the Fourier basis, exposing periodicities and correlations in the amplitudes. The hidden subgroup (HSP) leaves signatures in the QFT, which algorithms then use to uncover the secret rules efficiently

- HSP → finds the hidden rule that governs the system

Depending on the hidden rule, we implement the correct algorithm to reveal more information about it:

- Shor → finds hidden patterns (periodicity) in integers

- Simon → finds hidden correlations (relationships) in binary strings

Search & Optimization [Quantum Walk-Based Family Algorithms]

This category includes algorithms designed to efficiently explore large or complex solution spaces. Rather than checking each possibility individually, quantum algorithms use superposition and interference to amplify promising solutions while suppressing unlikely ones. This makes them well suited for unstructured search, optimization problems, and path finding, where the goal is to locate optimal or near optimal solutions with fewer evaluations and parsing than classical approaches.

Grover’s Algorithm

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Search problems where you want to find a marked item in an unsorted database.

- Optimization problems where you want to locate the best solution among many possibilities.

- Can be generalized via Amplitude Amplification to improve probabilities for any oracle-based problem.

- Eliminates the need for classical parsing or step-by-step search functions, because the algorithm “walks” the solution space and amplifies the correct answer directly.

How it Works

- Starts with a superposition over all possible states (like all database entries).

- Uses amplitude amplification, or equivalently a quantum walk, to increase the probability of the correct state while suppressing incorrect states.

- Each iteration applies phase inversion and inversion about the mean, producing constructive interference on the marked state and destructive interference on the rest.

- After roughly √N iterations, measuring the system gives the correct state with high probability.

When to Use It and Why

- Best for unstructured search and combinatorial optimization, where classical brute force is too slow.

- Works whenever you can define an oracle that flags “correct” solutions.

Amplitude Amplification [The Oracle’s Home (Blackbox)]

Primary Idea

Amplitude amplification is a general quantum technique for boosting the probability of “good” states in a superposition. The oracle is its “home” because it defines which states are considered good and therefore eligible for amplification. It is the framework behind quantum search and optimization algorithms that knows which outcomes to amplify. Sometimes it is referred to as a black box

How It Works

- Start with a superposition of all possible states.

- The oracle flags the “good” states by flipping their phase.

- The amplitude amplification steps (reflections about the average amplitude) increase the probability of the flagged states while decreasing the probability of all others.

- Repeat the process iteratively. After enough rounds, measuring the system gives a correct state with high probability.

Key Insight

- The oracle is embedded in the search or optimization algorithm: it’s the source of the “good vs. bad” distinction that amplitude amplification relies on.

- Grover’s algorithm is a special case of amplitude amplification where the oracle identifies a single marked item in an unsorted database.

- This technique removes the need for parsing or step-by-step checking, because the algorithm naturally amplifies the desired outcomes using interference.

- Amplitude Amplification is a quantum walk applied to identification, while Grover’s algorithm is a quantum walk applied to searching that uses AA’s identification to find the marked item

When to Use It

- Whenever a quantum procedure or subroutine has clearly defined “good” outcomes and you want to boost their probability efficiently.

- Ideal for search, optimization, or probabilistic quantum subroutines.

Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA)

Primary Idea

- QAOA is a quantum walk applied to combinatorial optimization problems.

- Instead of searching for a single marked item, it guides amplitudes toward high-quality solutions across a complex solution space.

- Uses alternating operations (phase separation + mixing) to steer the quantum system toward optimal or near-optimal configurations.

How it Works

- Encode the optimization problem into a cost function that evaluates solution quality. (low cost functions are preferred to high cost functions)

- Initialize a superposition of all possible solutions.

- Apply alternating operators that adjust phases and mix states, forming a guided quantum walk.

- After a fixed number of steps, measure the system — high-probability outcomes correspond to good solutions.

When to Use It and Why

- Best for combinatorial optimization, scheduling, or resource allocation problems where classical algorithms would take too long to explore all possibilities.

- Intuition: think of it as a smarter quantum walk that doesn’t just amplify a single “good” state, but navigates the landscape of solutions, pushing probabilities toward the best ones.

Connection to AA and Grover

- QAOA is part of the Quantum Walk-Based Family, like Grover and amplitude amplification.

- While AA identifies good states and Grover finds a single marked item, QAOA guides the walk across many states to optimize an objective function.

Quantum Walk-Based Algorithms [Umbrella of Search, Optimization, and System Navigation]

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Quantum walk algorithms are a general framework for quantum algorithms that explore large solution spaces efficiently.

- They improve upon classical search and optimization by allowing probability to flow through the system via interference, rather than checking states one by one.

- This makes them especially powerful for unstructured search, optimization, graph traversal, and decision problems where evaluating every possibility is infeasible.

Instead of inspecting outputs individually, quantum walks reshape the entire probability landscape to highlight desirable outcomes.

How it Works

- Start with a superposition representing all possible states or solutions.

- Through carefully designed phase shifts and interference, probability amplitudes “walk” through the space, reinforcing useful paths and suppressing irrelevant ones.

- An oracle or cost function defines what counts as “good,” “target,” or “low-cost” states.

- Repeated evolution causes constructive interference around optimal solutions, allowing them to emerge with high probability upon measurement.

- The main idea: the algorithm guides the system’s movement through the space, rather than evaluating each location independently.

Connection to Specific Algorithms

Amplitude Amplification:

The foundational mechanism behind quantum search. It identifies which states are desirable (via an oracle) and amplifies their amplitudes, shaping the direction of the quantum walk.

Grover’s Algorithm:

A quantum walk applied to searching. It uses amplitude amplification to find a marked item in an unstructured space with far fewer evaluations than classical search.

QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm):

A guided quantum walk applied to optimization. Instead of marking a single solution, it uses a cost function to bias the system toward low-cost, efficient solutions across the entire landscape.

In other words: quantum walks are the container; amplitude amplification, Grover, and QAOA are specific ways of navigating solution spaces depending on the goal.

When to Use it and Why

- Use quantum walk algorithms when the problem involves searching, optimizing, or navigating large or unstructured spaces.

- Ideal for database search, routing, scheduling, combinatorial optimization, graph problems, and decision-making systems.

- Powerful because they reduce or eliminate the need for classical parsing, iteration, or exhaustive evaluation by letting interference do the work.

Intuitive Process Flow

Quantum Walk → defines how probability moves through the solution space

Amplitude Amplification → identifies which states should be reinforced

Depending on the goal, we implement the appropriate algorithm to guide the walk:

Grover → finds a specific target in an unstructured space

QAOA → finds high-quality or optimal solutions by reshaping the entire system

Simulation & Modeling

Simulation and modeling algorithms use quantum systems to represent and study other quantum or highly complex systems. Classical methods often struggle to capture all interactions efficiently, but quantum computers can naturally encode and evolve these systems in superposition. This approach is especially useful in chemistry, materials science, and physics, where understanding system behavior depends on accurately modeling fundamental interactions and dynamics.

Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE)

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Used to extract precise phase and energy information from quantum systems.

- Central to simulation and modeling tasks, especially in physics and chemistry, where understanding system energies is critical.

- Forms the backbone of many higher-level algorithms, including Quantum Hamiltonian Simulation and parts of Shor’s algorithm.

- Provides exponentially more efficient access to phase information compared to classical sampling methods.

- Instead of observing a system repeatedly and inferring behavior statistically, QPE reads phase information directly from the quantum evolution itself.

How It Works

- Starts with a quantum state that evolves according to some operation or system rule.

- As the system evolves, it accumulates a phase that encodes information about that system, such as its energy.

- QPE uses interference and controlled evolution to transfer that hidden phase information into measurable qubits.

- When measured, these qubits reveal the phase value with high precision.

- The key idea is that phase is not measured directly. It is inferred from how amplitudes interfere over time.

- Rather than tracking outputs step by step, QPE reads the system’s internal rhythm.

When to Use It and Why

Best used when you need precise information about a system’s internal behavior, such as energy levels or eigenvalues, when you need to keep the main quantum state intact.

- Ideal for quantum chemistry, materials science, and physical simulations where accuracy matters more than approximation.

- Most powerful when you already have a good representation of the system and want to extract exact properties from it.

- QPE is chosen when understanding the system itself is the goal, not just finding an optimal answer.

QPE reads the system’s internal rhythm without collapsing it, extracting precise phase or energy information via auxiliary qubits while keeping the main quantum state intact. It does this by analyzing the system’s matrix and its eigenvalues, revealing the natural “flow” and strength of the system.

Example: By measuring the phase evolution of an ancilla qubit, we can determine what gates or adjustments to apply to the main system before errors accumulate, without ever directly disturbing it.

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Hybrid quantum–classical algorithm for approximating ground states (rest state) of quantum systems.

- Reduces the need for full-scale, error-free quantum hardware and makes simulation feasible on current or soon-to-be devices.

- Useful when exact phase/energy information is hard to extract directly (like QPE), but an approximate solution is sufficient.

- Iteratively improves estimates by combining quantum evaluation of the system with classical optimization.

How It Works

- Prepare a parameterized quantum state representing a guess for the system’s ground state.

- Measure the system to estimate its energy (or other cost function) via repeated trials.

- Feed the measurement results into a classical optimizer to adjust the parameters for the next iteration.

- Repeat this cycle until the parameters converge to minimize the energy, approximating the true ground state.

- Main idea: let the quantum system explore possibilities while the classical algorithm guides it toward optimal solutions.

When to Use It and Why

- Best used when near-term quantum hardware is available but full-scale QPE isn’t practical.

- Ideal for quantum chemistry, materials science, and molecular modeling where approximate ground states are sufficient.

- Most powerful when the system is too large or noisy for exact phase estimation but you still need meaningful insight into its energy landscape.

- VQE effectively lets the system “feel out” its optimal configuration, guided by classical computation.

Quantum Hamiltonian Simulation (QHS)

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Directly simulates how a quantum system evolves over time according to its Hamiltonian (the operator that governs the system’s energy and dynamics).

- Essential for studying physical, chemical, or material systems that are too complex for classical simulation.

- Provides insight into time-dependent behavior, reaction dynamics, and energy transitions in a system.

- Can be used to predict system evolution, test control strategies, or model new materials efficiently.

How It Works

- Encode the system’s Hamiltonian into a quantum circuit.

- Initialize a quantum state representing the system’s starting configuration.

- Evolve the state according to the Hamiltonian over discrete time steps using quantum gates.

- Measure relevant properties of the system (like energies, populations, or observables) after evolution.

- The key idea: the quantum computer naturally follows the system’s evolution, avoiding the exponential overhead classical computers face for large systems.

When to Use It and Why

- Best used when classical simulation is impractical due to system size or complexity.

- Ideal for physics, chemistry, and materials science where predicting exact time evolution or reaction dynamics is crucial.

- Most powerful when you need to understand the system’s behavior over time, rather than just static properties like ground state energy.

- QHS is chosen when simulating the actual dynamics of a system is the goal, not just estimating static quantities.

- Most powerful when you want to simulate the actual physical behavior of a system over time, such as testing new materials, chemical reactions, or molecular dynamics, rather than just approximating static properties.

Linear Algebra & Machine Learning (Data Analysis)

These algorithms focus on efficiently manipulating high-dimensional vectors and matrices, which are central to data analysis and machine learning tasks. Quantum computers can process large state spaces in parallel, allowing certain operations, like solving linear systems, extracting principal components, or performing pattern recognition to be done more efficiently than classically possible. The emphasis is on capturing global structure and correlations in data, not on processing individual data points.

HHL Algorithm (Harrow-Hassidim-Lloyd)

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Solves linear systems of equations exponentially faster than classical algorithms for certain high-dimensional cases.

- Useful in physics simulations, engineering, finance, and machine learning applications that rely on solving large linear systems.

- Provides access to global properties of the solution without needing to explicitly compute every component.

- HHL extracts the global flow of a quantum system, providing the information needed to act on it later, without altering the system directly

How It Works

- Encode the matrix of the linear system as a quantum operator.

- Uses Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) and ancilla qubits to find eigenvalues of the matrix.

- Matrix → network of relationships between vectors

- Eigenvector → the “flow direction” of the system

- Eigenvalue → how strong or pronounced that flow is

- **Eigenvalues are incredibly important in predictive algorithms due to this**

- A matrix represents the relationships between multiple vector points, and an eigenvector is a direction that naturally aligns with the matrix’s action, while the eigenvalue tells you how strongly the matrix stretches or scales that direction

- Rotate amplitudes based on the eigenvalues to encode the solution in the quantum state.

- Measure the quantum state to extract relevant properties or expectations of the solution.

When to Use It and Why

- Best when dealing with very large, sparse, or structured linear systems where classical methods are inefficient.

- Ideal for machine learning or scientific simulations where accessing the full solution explicitly isn’t required, only certain global features or observables.

- Powerful because it leverages quantum parallelism to capture correlations and structure across the entire system simultaneously.

- Quantum Parallelism: the ability of a quantum computer to act on all components of a system simultaneously, allowing the global behavior of the system to be altered or analyzed at once, rather than handling each component individually

Quantum Principal Component Analysis (qPCA)

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Extracts the main directions of variation (principal components) in high-dimensional quantum data.

- Helps identify dominant patterns or correlations in large datasets efficiently.

- Can provide exponential speedups over classical PCA for very large state spaces.

How it Works

- Encodes classical or quantum data as a density matrix in a quantum system.

- Uses QPE to estimate eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the density matrix.

- Eigenvectors correspond to the principal components; eigenvalues indicate their importance or weight.

- The quantum system processes all components in superposition, capturing global structure without iterating over individual entries.

When to Use It and Why

- Ideal for analyzing complex, high-dimensional datasets where classical PCA would be too slow.

- Unlike HSP, it’s not looking for hidden relationships in a system, but to understand the dominant patterns of dataflow and correlations in a quantum system.

- Useful in machine learning, pattern recognition, and data compression.

- Provides system-level insight into data correlations, which can then guide downstream algorithms (like QSVM or clustering).

Intuition

- Think of it as finding the flow directions in your data: qPCA tells you which patterns dominate and how strongly they influence the system, similar to how HHL reveals the flow in linear systems.

- It’s about seeing the big picture first, then deciding how to act on it

Quantum Support Vector Machines (QSVM)

Primary Uses and Improvements

- Classification problems where the goal is to separate data into distinct groups.

- Pattern recognition in high dimensional datasets where classical feature spaces become expensive or impractical.

- Useful when the structure of the data is complex and separation depends on correlations across many dimensions rather than obvious features.

- Potential advantage comes from accessing very large feature spaces efficiently using quantum states.

How It Works

- Classical SVMs work by finding a boundary, or hyperplane, that best separates data into classes.

- QSVM maps classical data into a high dimensional quantum feature space using quantum states.

- In that quantum space, data points that are hard to separate classically may become easier to separate because the structure is expanded.

- The algorithm evaluates similarity between data points using quantum kernels, capturing global correlations rather than individual features.

- Measurement then determines the classification boundary that best separates the data.

When to Use It and Why

- Best used when classical machine learning struggles due to dimensionality or complex correlations.

- Useful when patterns exist in the relationships between features rather than in individual data points.

- Applies to anomaly detection, pattern recognition, and classification tasks in large or complex datasets.

- QSVM is chosen when understanding separation and structure in data is more important than interpretability of individual features.

Intuition

- QSVM doesn’t look at data point by point.

- It looks at how data points relate to each other in a very large feature space, using quantum states to represent and compare those relationships efficiently.

- QSVM uses HHL and qPCA both to build a map and determine the boundaries and segregation points of data

Linear Algebra & Machine Learning Final Thoughts

Let’s use an analogy to best understand what happens within quantum data analysis algorithms. Imagine a mountain range.

- HHL maps the flow of the rivers (system directions).

- qPCA identifies the tallest peaks and valleys (dominant patterns).

- QSVM draws the contours that separate different regions (classification boundaries).

Quantum Systems Analysis and Data Extrapolation (QFT, HSP, QPE, qPCA and more…)

Mapping the Algorithmic Ecosystem

Let’s go over an important part of quantum algorithms. We can use some of these algorithms to gain a better understanding of the ways we can influence both quantum systems and data.

To implement quantum algorithms effectively, we first need to understand the system. The following tools, techniques, and frameworks extract system-level information, reveal hidden structures, or model internal behavior, guiding the optimal placement of algorithms.:

QFT (Quantum Fourier Transform) → transformation →

transforms the qubits from the computational basis into the Fourier basis, exposing periodicities and correlations in the amplitudes.

HSP (Hidden Subgroup Problem) → algorithmic framework →

finds the hidden rule that governs the system, revealing structural patterns that algorithms can exploit.

QPE (Quantum Phase Estimation) → analysis / measurement →

extracts phase/eigenvalue information from the system without collapsing it, reading the internal rhythm via auxiliary qubits.

qPCA (Quantum Principal Component Analysis) → analysis →

extracts systems level insight into data correlations for use with machine learning, pattern recognition, and data compression.

Quantum Phase Kickback → mechanism / tool →

encodes phase information from the system onto ancilla qubits, enabling extraction of eigenvalues or periodicity without disturbing the main quantum state.

Bell Basis / Entanglement Measurements → analysis / correlation tool →

reveal correlations and relational structure in multi-qubit systems without fully collapsing them, foundational for teleportation and QKD.

Amplitude Estimation → probability analysis →

measures the probability amplitudes of specific states in superposition, providing insight into which outcomes are most likely.

Quantum Walk Analysis → exploration / mapping tool →

explores the structure of a system or graph in superposition, mapping paths, connectivity, or optimal routes efficiently.

Variational Parameter Mapping → hybrid learning tool →

in hybrid algorithms (like VQE/QAOA), classical optimization interprets system-level responses to parameter changes, effectively learning the system’s behavior indirectly.

Implications of Quantum Algorithms and Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC)

If you’ve heard the word quantum recently, you’ve probably also heard about how it’s projected to break everything. It’s even being referred to as: Q-DAY. For me, it is reminiscent of Y2K. People made a lot of money off of the fear factor with Y2K.

But, I don’t think it’s as innocuous as Y2K was. Quantum computing probably really can break classical encryptions… eventually. None of this has happened yet, and I think before it gets to that point we will probably have discovered a solution to the problem that is better than what is currently being used. Let’s look at some quantum security theory, though. Let’s look at how these algorithms and tools would be implemented to break security.

The Tools That Break

Attacks are rarely about guessing secrets. They’re more often about learning the systems and structures that can disable or bypass security entirely.

Let’s take an honest look at the quantum algorithms, frameworks, architecture, or data analysis techniques that are likely to play a part in forcing the classical security landscape to eventually retire:

Attack Algorithms

Shor’s Algorithm

Targets cryptosystems whose security relies on the difficulty of factoring large integers or solving discrete logarithms. It doesn’t attack keys directly, it breaks the mathematical trapdoor those systems are built on.

Simon’s Algorithm

Less about deployed cryptography and more about structural weakness exploitation. It shows that hidden correlations can exist in functions that look random classically. This matters for protocol design and for understanding why “looks random” isn’t always enough.

Grover’s Algorithm

Doesn’t break encryption outright, but it halves the effective security of symmetric systems by accelerating brute-force and hash preimage searches. That’s why key sizes double in post-quantum recommendations.

Foundational Frameworks / Umbrellas

Hidden Subgroup Problem (HSP)

This is the umbrella. It explains why Shor and Simon work at all. If an encryption scheme leaks structure that can be modeled as a hidden subgroup, quantum algorithms can exploit it even if that structure isn’t obvious at the surface level.

Quantum Walk Frameworks

Explore structured spaces (graphs, networks, state transitions) in superposition. These algorithms can weaken cryptographic schemes that rely on assumed traversal hardness or obscured structural connectivity.

System Level and Structural Analysis Tools

qPCA (Quantum Principal Component Analysis)

This is where things move from “breaking math” to breaking implementations and data behavior. qPCA doesn’t crack keys, it can reveal dominant patterns, correlations, or flows in encrypted or partially processed data, especially at scale. That’s a system-level concern, not a cipher-level one.

Amplitude Estimation

Precisely measures probability amplitudes in quantum states. This can accelerate statistical analysis, bias detection, and probabilistic attacks, potentially strengthening side-channel or leakage-based vulnerabilities.

Phase Kickback / Interference-Based Techniques

Encode system information into quantum phases rather than measurements. These mechanisms underpin many cryptographic attacks by extracting structure indirectly, without collapsing the system.

Implementation and Architecture Vulnerabilities

Implementation-Level Quantum Analysis

Uses quantum tools to analyze noise patterns, timing behavior, and error distributions. These don’t break cryptography mathematically, but can expose real-world weaknesses in how secure systems are implemented.

The Real Problem with Classical Cryptography

The core limitation of classical cryptography has always been its linear nature. Classical computing itself is built on constraints that exist within a human constructed framework. Rather than working directly with the laws of nature, we imposed artificial boundaries, forcing security systems to operate within a strict binary view of reality: 1s and 0s. As a result, all computational expression within these systems is inherently constrained.

Nature does not operate in black and white. Reality is full of variance, uncertainty, anomalies, and outliers. These are not edge cases in the natural world, they are the norm. Quantum computing is powerful precisely because it can harness these characteristics rather than suppress them. Instead of forcing computation into a simplified, two-dimensional model, quantum systems rely on the actual behavior and limits of physics itself to define what is possible.

Because of this shift, much of post-quantum cryptography is already moving toward approaches that more closely align with natural systems. New encryption methods increasingly attempt to leverage physical principles rather than abstract mathematical rigidity. Hybrid cryptographic models that integrate both classical and quantum elements are becoming more common as researchers recognize that no single paradigm fully captures reality.

Ultimately, adopting quantum computation requires accepting that not everything can be cleanly defined or fully isolated. Ambiguity, probability, and emergence are not flaws in the system, they are features of how nature has always worked. Embracing that perspective is essential to unlocking the real potential of quantum computing and the cryptographic systems built upon it.

Why QKD, Lattice Encryption, and Classical Hybrid Cryptography Is Not Enough

Quantum Key Distribution, lattice-based encryption, and hybrid classical–quantum cryptographic models are often presented as the definitive answer to the quantum threat. They are important advances, and they significantly raise the bar against known quantum attacks. But they are not a final solution.

QKD addresses key exchange, not the broader cryptographic system. It ensures that keys can be distributed securely using quantum principles, but it does not protect how those keys are stored, used, rotated, or integrated into larger protocols. QKD also introduces practical limitations: specialized hardware, distance constraints, and infrastructure requirements that make large-scale deployment difficult. Most importantly, it does not solve algorithmic vulnerability at the system level.

Lattice-based encryption is currently one of the strongest candidates for post-quantum security, but it still operates within a classical mathematical framework. Its security relies on assumptions about computational hardness, not physical guarantees. As quantum algorithms evolve and as system-level analysis improves, those assumptions may weaken, especially when encryption is deployed at scale and exposed to real-world data patterns rather than idealized models.

Hybrid cryptographic systems attempt to bridge the gap by combining classical and quantum-resistant techniques. While this approach improves resilience in the short term, it also increases complexity. More layers mean more interfaces, and more interfaces mean more opportunities for structural weaknesses, misconfiguration, or indirect leakage. Hybrid systems often protect individual components without fully addressing how information flows across the entire system.

The deeper issue is that all three approaches largely focus on protecting outputs rather than understanding structure. They defend against known attack models, but they do not account for future algorithms that analyze relationships, correlations, and system-level behavior. As quantum computing matures, the most powerful attacks will not look like brute force or direct decryption attempts. They will target the underlying structure that gives rise to security in the first place.

True post-quantum security will likely require more than stronger keys or harder math problems. It will require cryptographic architectures designed with quantum-native thinking from the ground up, systems that assume structural analysis is possible and adapt accordingly. QKD, lattice encryption, and hybrid models are necessary steps, but they are transitional. They buy time, but they don’t close the door.

A Proposed Solution

We need to start really understanding the architecture of quantum security and quantum computing in general. (Yes, that’s why this tutorial exists) From that understanding we can begin to craft novel cryptographic solutions that involve harnessing the natural laws of physics and our universe to secure our systems and data.

The architecture of quantum computing isn’t one we will create, because it already exists. We have to find a way to work with nature and the laws that govern our reality to orchestrate solutions in unison. Building a playground like we did with classical computing, where we aimed to exercise total control over outcomes, will not work. Instead, we must work with the natural order presented to us and find ways to harness the inherent attributes of quantum computing to create integrated solutions.

This is ultimately the direction we are heading in, and it is the premise behind the exploration into the entire tutorial series: Building a Quantum Cipher. We’re exploring the architecture of quantum systems to understand them holistically and build novel solutions to the limitations we faced with classical computing. Quantum computing forces us to think bigger. It forces us to see that there is more, more structure, more nuance, and more possibility.

Next time, in Part 5, we’ll focus on exactly that: Quantum Architecture and how these pieces fit together, specifically for security and development. We’ll explore the full depths of what’s possible and consider how to integrate the natural laws of physics into novel solutions.

Leave a Reply