Introduction

So far, we have learned hands-on about gates and their relationship to the physical world. By now, you should understand that quantum programming is more than just writing code. It is part of operational technology (OT) that directly controls real quantum systems and their states.

With this in mind, we can now explore the different gates, providing a brief description of how each functions programmatically, as well as touching on the multi-gate functions and the mathematics generated by these interactions.

Remember: a gate is simultaneously a programming, mathematical, and physical activity. It is a system of events that interacts and unfolds to produce a result, with that event typically being an action that changes the state of a qubit. By understanding these three “gate pillars” we gain the ability to shape how quantum operations unfold and ultimately influence the outcomes of our projects.

Probability Amplitudes, Rotation, Phase, Waveforms and Interference Patterns

We’ve gone over probability amplitudes and rotation before in Project 1 and Project 1 Reflections, but I will touch on them again and also introduce phase and interference types. You’ll need a solid grasp of these concepts to understand how gates work and how to properly implement them.

Probability Amplitudes

A probability amplitude is a complex number whose magnitude (intensity) determines the probability, or the likelihood of an event occurring. Breaking it down further: Amplitude and intensity are the same concept. For example, decibels are a measure of sound amplitude. The louder the sound, the higher the amplitude, and therefore, higher the decibels. So, when a probability amplitude is increased, so is the likelihood of the related event occurring.

Example: We altered the probability amplitude of a qubit collapsing by introducing the qubit to a Hadamard gate. It changed the probability of classical collapse to 50% for both 0 and 1. By applying the H gate, we split the probabilities across multiple paths and altered the amplitude.

Rotation

Rotation is what we measure, oftentimes indirectly, to determine what state a qubit is in. Think back to the Project 1 Reflections we went over and to NV Centers in diamonds and electrons. We measure the spin state of an electron/qubit when it emits a photon after being excited by a laser, and from there it collapses into a 0 or a 1. Rotation can be impacted by gates or physical changes to the environment around the qubit, or by direct interaction. This can involve changing the tilt or twist of a qubit using those gates.

Phase

Phase represents the timing of a qubit’s probability amplitude along its waveform, much like the crests and troughs of ripples in a pond. If two ripples (probability amplitudes) are in sync, their crests and troughs combine and they interfere constructively, amplifying the overall ripple. If they are out of sync, the crests of one may coincide with the troughs of another, causing destructive interference, which weakens or cancels the overall ripple. Partial alignment produces a mix of both effects.

This helps illustrate that phase itself doesn’t change the amplitude of a single qubit but determines how multiple qubits combine to produce interference patterns.

Interference Patterns

Interference patterns are the resulting measurement of two or more probability amplitudes coming together. For example, if we dropped two pebbles into a lake and the waves (probability amplitudes) rippled outward, when they crossed, they would create a new wave together (interference pattern) influenced by both ripples. If we also dropped the pebbles at different angles, we could change the phase shift and thus alter the resulting patterns.

There are different interference pattern types, just like the ripples we would see with the pebbles are different. Constructive interference is when the probability amplitudes align in phase (+), adding together and increasing certain measurement outcomes. Think of the ripples going even further together and being even stronger. Destructive interference happens when the probability amplitudes are out of phase (-) and cancel each other out, reducing certain measurement outcomes. Think of the ripples canceling each other out and not traveling very far or being visible. Partial interference occurs within the grey area of both, where amplitudes are partially aligning in some ways and cancelling in others. Most real multi-qubit systems produce partial interference across many qubits, creating patterns that can be exploited in QPUFs or entanglement based cryptography. If these patterns are stable and insufficiently randomized, then these operational vulnerabilities can be exploited by observers repeatedly extracting statistical data and using it to infer the system or methods used to create the encryption. These can then later be exploited via quantum emulation tactics.

Keep these concepts in mind when we go into single-qubit gates and the three pillars of gate functions: programming, physical, and mathematical.

Single-Qubit Gates

Let’s go over the different types of single qubit gates that exist. Expand each gate to learn about how it’s commonly used, and it’s programming, physical, and mathematical layers.

X Gate (Pauli-X)

Programming: Flips a qubit’s state from |0⟩ → |1⟩, or vice versa. Think of it as a classical NOT

Physical: Physical: 180° rotation around the X-axis on the Bloch sphere; swaps probability amplitudes of |0⟩ and |1⟩

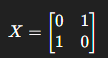

Mathematical:

Application: Used in Grover’s search by ‘marking’ the target state by flipping the bit and creating contrast. Grover’s search algorithm is used to search unsorted databases more quickly than classical searches. It uses superposition, interference, and phase rotations to amplify the probability of the correct answer. Also flips the waveform along the X-axis; amplitudes are swapped. This flip helps create unique interference patterns, which can be used to build a basis of quantum fingerprinting in cryptography.

Y Gate (Pauli-Y)

Programming: Flips the qubit and applies a 90° phase change

Physical: 180° rotation around the Y-axis; combines flip and phase twist

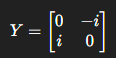

Mathematical: It combines the amplitude swap of X with a complex phase factor, crucial for certain interference patterns

Application: Preparing a qubit for interference experiments where both amplitude and phase need to be controlled, such as in certain error-correcting routines. It can maintain qubit integrity in noisy systems. It can be used in conjunction with X, Z, and CNOT gates to detect and correct errors across multiple qubits. This helps preserve decoherence (superposition).

Z Gate (Pauli-Z)

Programming: It’s used when you want to adjust relative phase without changing measurement probabilities directly

Physical: Rotation around the Z-axis of the Bloch sphere by 180°. The qubit “twists” in place—no flip along the X or Y axes, just a phase adjustment

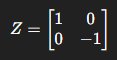

Mathematical: It inverts the amplitude of |1⟩ while leaving |0⟩ the same, affecting interference patterns when combined with other gates

Application: Used in phase adjustments for quantum algorithms. Can be used in Grover’s search as part of the diffusion operator, reflecting amplitudes about the average and target state. Used in error correction by correcting phase-flip errors on qubits and multi-qubit routines, especially when used with X and Y gates in multi-qubit routines. Used when precise interference is required, in entanglement preparation and quantum Fourier transform (QFT). Also assists in altering waveform patterns that create unclonable functions.

H Gate (Hadamard)

Programming: Creates superposition. It’s used whenever you want a qubit to explore multiple states simultaneously

Physical: Rotates the qubit halfway between the X- and Z-axes on the Bloch sphere, placing it on the equator. This prepares the qubit for interference with other qubits

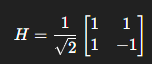

Mathematical: Converts a definite state into an equal-weight superposition with a relative phase difference (50/50, remember?), which is critical for entanglement and interference patterns

Application: Superposition initialization. Used at the start of quantum algorithms or quantum teleportation to allow qubits to simultaneously explore multiple states. Entanglement Preparation: when combined with CNOT, H gates can create Bell states. Waveforms: The H gate puts the qubit into a superposition, effectively splitting its amplitude across multiple paths. These amplitudes interfere with other qubits’ amplitudes to generate unique interference patterns, which is particularly important in cryptography.

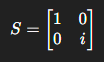

S Gate (Phase)

Programming: In code, it’s used when you need to adjust relative phase between |0⟩ and |1⟩ without changing measurement probabilities directly

Physical: Rotates the qubit around the Z-axis of the Bloch sphere by 90°. The qubit’s amplitude remains the same; only the phase changes

Mathematical: The |1⟩ amplitude acquires a factor of i, which modifies interference in multi-qubit circuits

Application: Phase adjustment in algorithms, shaping constructive and destructive interference. Entanglement tuning with multi-qubit states, ensuring correct interference and complementing CNOT and H operations. The S gate twists the qubit’s waveform along the Z-axis, find tuning interference across qubits. Essential for generating multi-qubit waveforms used in cryptography and error correction.

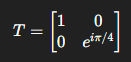

T (π/8 Phase)

Programming: Used in code when you need fine-tuned phase adjustments to control interference patterns in multi-qubit circuits

Physical: Rotates the qubit around the Z-axis by 45°. Unlike S (π/2), this is a smaller rotation, giving finer control

Mathematical: The |1⟩ amplitude acquires a factor of eiπ/4, adjusting interference subtly without affecting |0⟩

Application: Phase Tuning in Algorithms: Used in Fourier transform, Shor’s algorithm, and other interference-based routines. Used in entanglement & multi-qubit functions by fine tuning waveform interference in conjunction with H, S, CNOT, or other gates to produce unique patterns for cryptographic functions or unclonable states. Enables precision phase control in QPUFs, Bell-state manipulations, and other waveform-based cryptographic routines. Small phase adjustments like T make cloned patterns nearly impossible to replicate, enhancing security.

Multi-Qubit Gates

These are gates that operate on two or more qubits simultaneously. They create correlations and entanglement that single-qubit gates cannot and open totally new pathways we haven’t dived into just yet.

Correlation in gates refers to the phenomena when the measurement of one outcome gives information about the other. For example, back to our pebbles being dropped in the water, when we create a new interference pattern based on the two original pebbles creating ripples in the water, we can then infer things about each individual pebble using the right mathematical functions and logical deductions. This ability to logically deduce happens classically all the time. A good example is in algebra, when we solve for a specific variable based off of information we have about other variables interacting. The difference between this and entanglement is that in entanglement, information about each single qubit doesn’t exist independently. They are inextricably linked, like two ripple patterns in water that only can form a pattern together.

Entanglement is a special type of correlation that exists only in quantum systems. It introduces maximal correlation, meaning that the qubits’ measurement outcomes are perfectly linked: when considered as a whole system, the measurement result of one qubit is fully correlated with the result of the other. It also introduces indistinguishable individuality, which means to say that each qubit alone appears to be completely random, even though they exist together. The only way to realize that they aren’t completely random is to observe their global property, which is the combined system created by both qubits being entangled with one another.

With entanglement: Imagine two pebbles created and joined by the rules of the pond (the quantum system) itself. Suppose you drop one pebble, and the other pebble on the other side of the pond is also dropped, creating ripples across the pond. Each pebble alone seems to produce random ripples you can’t make sense of, because you aren’t looking past your own pebbles ripples. The interference pattern (ripple) looks completely random independently. However, when you step back and observe the entire pond from above, the ripples reveal a clear pattern that makes sense. Just like the pebbles, each entangled qubit alone seems random, but their behavior is fully correlated when viewed as a combined quantum system.

A few different types of multi-qubit gates allow us to create these entangled quantum systems. We are going to go over the most commonly used gates that provide the building blocks for entanglement. However, more in-depth analysis of entanglement and teleportation will occur after Project 2 is completed and we do project reflections. Click each gate below to expand the section.

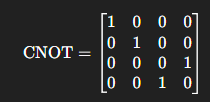

CNOT (Controlled-NOT) Gate

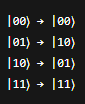

Programming: Core building block for entanglement, teleportation, and QEC (Quantum Error Correction) circuits. The CNOT gate is applied by designating one qubit as the control and another as the target. When the control qubit is in the ∣1⟩ state, the target qubit is flipped; otherwise, the target remains unchanged

Physical: Links two qubits so that rotations or interactions of one qubit directly influence the other, creating correlated states. Wavefunctions overlap via Hamiltonian in Hilbert space in such a way that their probabilities are no longer independent. The two qubits become a global object that must be changed on the system level

Mathematical: Adds off-diagonal elements to the two-qubit state matrix, enabling superposition and correlation in a combined system

Top-left 2×2 block = control is ∣0⟩ → target unchanged

Bottom-right 2×2 block = control is ∣1⟩ → target flips

Application: Used in Bell-state creation after entanglement, quantum teleportation, and error-correcting codes; CNOT enables secure quantum protocols by creating entanglement and non-clonable correlations that are foundational to QKD, quantum fingerprinting, and controlled teleportation.

Example: Start with two qubits, one is a control and the other is a target. Apply a Hadamard gate and put the qubit into superposition. Apply CNOT gate with both the control and target. The qubits become entangled and then form a Bell-state

SWAP Gate

Programming: Exchanges the states of two qubits across a quantum system. If qubit A is |0⟩ and qubit B is |1⟩, after the SWAP, A is |1⟩ and B is |0⟩. Often implemented using three CNOT gates in sequence

Physical: The qubits’ wavefunctions are effectively exchanged. Hamiltonian dynamics or control pulses physically swap the quantum information between two qubits via teleportation. The operation itself does not perform measurement

Mathematical: Represented as a 4×4 unitary matrix that permutes the basis states

Can be decomposed as three CNOTs: CNOT(A→B), CNOT(B→A), CNOT(A→B)

Application: Routing quantum information when qubits aren’t physically adjacent in a circuit. Reordering qubits for algorithmic needs or error correction routines. Used in entanglement distribution and can swap entangled partners or adjust entangled paths. Has potential for use in secure quantum networking protocols, due to its ability to transmit quantum states (data) between nodes without revealing their origin, preserving entanglement and global system correlations.

Toffoli (CCNOT) [Controlled-Controlled NOT] Gate

Programming: Has two control qubits and one target qubit. Target qubit flips only if both control qubits are |1⟩; otherwise, it remains unchanged. Serves as a universal gate for reversible classical computation in quantum circuits. It can implement classical Boolean functions without losing information vis unitary operation. Introduces classical logic into quantum computing.

Physical: Links three qubits so that the target qubit’s state is conditioned on the joint state of the two control qubits. In hardware, involves multi-qubit interactions or decomposition into a series of single- and two-qubit gates. Wavefunctions overlap in Hilbert space, creating correlated rotations across all three qubits.

Mathematical: Represented by an 8×8 unitary matrix. Flips the target only for the |11⟩ control state combination. Can be decomposed into simpler gates (like CNOT and single-qubit rotations) for implementation on real quantum hardware.

Application: Error correction where logical qubit states depend on multiple physical qubits. Quantum arithmetic operations in algorithms, such as adders and modular arithmetic. Can enforce conditions on multiple qubits for QPUFs or secure state preparation, enabling complex entanglement patterns that are hard to predict or replicate, potentially useful in secure networking quantum protocols.

Controlled-Phase (CZ,CRk) Gates

Programming: A two-qubit gate with one control qubit and one target qubit. Applies a phase shift (commonly π for CZ) to the target qubit only if the control qubit is |1⟩. Leaves the target unchanged if the control is |0⟩

Physical: Introduces a phase shift in the wavefunction of the target qubit, conditioned on the control qubit. In hardware, realized through controlled interactions or tunable couplings that induce the phase shift. Wavefunctions overlap in Hilbert space, producing correlations that are phase-dependent rather than amplitude-flipping

Mathematical: Represented by a 4×4 unitary matrix. Can be generalized to arbitrary phase angles, not just π

Application: Entanglement preparation, often when paired with Hadamard gates to create Bell states or other entangled states. Essential in phase-based quantum algorithms such as Grover’s and QFT (Quantum Fourier Transform). Creates phase correlations that contribute to unclonable quantum fingerprints and controlled interference patterns, usable in cryptography.

After entanglement occurs via multi-qubit gate involvement, we can measure the entangled qubit system. For example, we can measure an entire two-qubit quantum system as follows: We use the concept of Bell states, created by John S. Bell (Bell here is not a mathematical function reference) in a BSM. When we perform a Bell-State Measurement (BSM), the two qubit system collapses into one of only four possible correlated states, which fully describes the system’s entangled correlations to us. Later, this state collapse and correlation measurement also act as the basis for us to perform quantum teleportation. We will go into more about BSM next.

Bell-State Measurement (BSM)

As mentioned before, BSM is the measurement of the state that exists between two qubits, or their correlations, not the qubits themselves. The measurement describes both the classical correlation and phase relationship between the qubits.

Recall the entangled pebbles in our earlier water example. We drop one pebble on one side of the pond, and then, some time later, the other pebble is dropped. If we only observe the ripples (waveform) from our first pebble, they appear random because we’re not accounting for how the other pebble’s ripples are influencing it, we just see seemingly chaotic crests.

When we zoom out to view the entire pond, we can see how the ripples from both pebbles interact and form coherent patterns together. This is where we introduce a Bell-State Measurement (BSM). BSM allows us to measure the entire pond, capturing how the two entangled pebbles create ripples together. It tells us both how the ripples are interacting to form new patterns (classical correlation) and whether the overlapping waves are reinforcing each other or cancelling out (phase relationship).

There are only two possible outcomes for each pebble if we look at the pebbles independently and classically:

- Each pebble (A or B) can have a positive or negative phase.

- Each pebble can have a classical state of 0 or 1.

But in a quantum system, we aren’t viewing the qubits classically or from the bottom up (individual qubit measurements). We are viewing it from the top down (quantum system measurements). Using BSM, we leverage the interactions and correlations of these system level ripples (waveforms) to understand not only how A and B behave together, but also what they originated as without ever measuring them independently. BSM provides a shortcut: it lets us see the pond ripple interactions, then deduce details about the individual pebble ripples by examining the overall conditions. This is also how quantum teleportation works: by observing the entire system, we can transmit enough information to reconstruct the quantum state elsewhere without measuring the individual qubits. The BSM enables this by collapsing the system into its four possible correlated outcomes:

- Φ⁺ = |00⟩ + |11⟩ (positive phase, qubits match)

- Φ⁻ = |00⟩ − |11⟩ (negative phase, qubits match)

- Ψ⁺ = |01⟩ + |10⟩ (positive phase, qubits do not match)

- Ψ⁻ = |01⟩ − |10⟩ (negative phase, qubits do not match)

As you can see, we aren’t concerned about whether or not the qubit is a 0 or a 1. We are concerned about the system-level measurement of these qubits interacting with one another. It doesn’t matter if qubit A is 0 or 1, or qubit B is 0 or 1. What matters is the relationship between them: whether their states match or differ, and how does their relative waveform phase influence the interference pattern? If the phases align, the interaction strengthens (+) the pattern; if they oppose, it weakens (−) it.

We can then use the information obtained from the BSM to reconstruct the missing individual qubit information, almost like quantum reverse engineering. Rather than measuring each qubit directly, we infer their original states from the system-level correlations and phase relationships. This is exactly what later enables quantum teleportation: the global measurement outcome provides the instructions needed to recover the quantum state elsewhere, without ever directly observing the original qubit itself.

In our next project (Project 2), we will be performing entanglement via multi-qubit gates, BSM and then quantum teleportation. Note: While BSM provides the necessary system-level information, teleportation itself is not inherent to BSM; it merely requires entanglement to exist beforehand.

But for now, why do quantum gates and their functions matter so much together?

Conclusions

Quantum gates matter most when considered together because they form a complete toolkit for controlling quantum systems. Single-qubit gates shape individual qubit states, creating superposition, phase, and interference. Multi-qubit gates link qubits through entanglement, generating correlations that only make sense at the system level. Together, these gates allow us to manipulate global quantum states, measure system-wide interactions with tools like Bell-State Measurement, and ultimately perform complex operations such as quantum teleportation. Understanding gates in concert gives us the ability to design, predict, and exploit quantum behavior in ways that are impossible classically, making them the foundation of all quantum computation and communication.

Leave a Reply